The Lesson We Refuse to Learn

I just saw that Kamala Harris came out with a new book. One can assume- I did not read the book- what was in it. I gleaned enough from reviews to know I could not actually sit and read it without needing to take a walk. Thank you – especially- Carlos Lozada. The book- It was a bit self-serving apology, a bit an excoriation, albeit mildly, of her mentor and boss the former President Joe Biden, and a smidge -an excuse as to why her message did not resonate with the Trump voters. But haven’t we seen this all before? Don’t we really know who the Trump voters are? Yes, we actually KNOW Trump voters. They have been with us as long as we have had our 4 million year old brains. (This is how my neuroscientist/ psychologist spouse describes the human brain). Hear me out…

____________________________

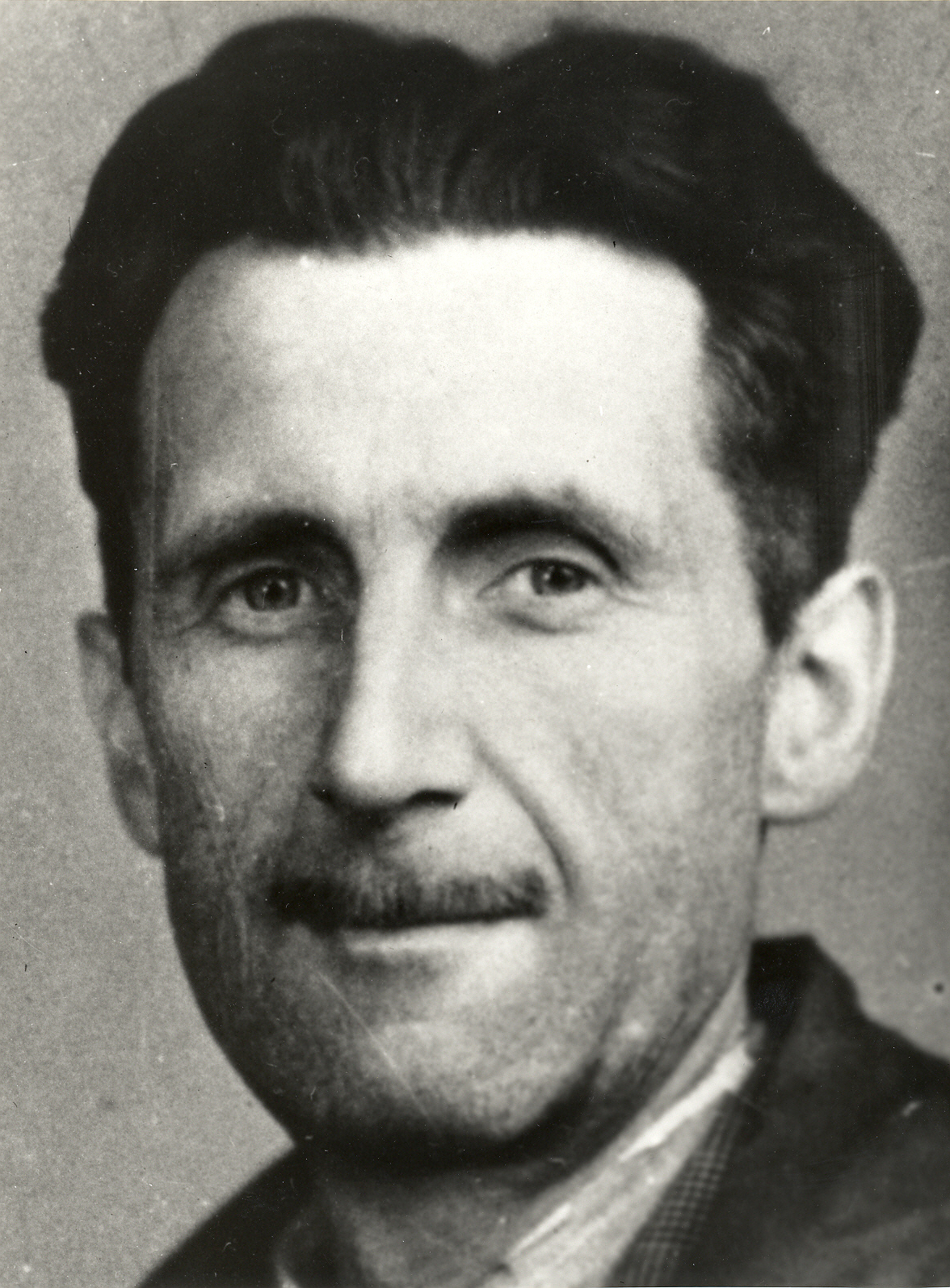

In 1941, as fascist movements swept across Europe, George Orwell observed something that liberal democracies still struggle to understand today. Writing in “The Lion and the Unicorn,” he identified a fatal blind spot in progressive thinking—one that would prove as relevant in 2024 as it was in 1941.

“Nearly all western thought since the last war, certainly all ‘progressive’ thought, has assumed tacitly that human beings desire nothing beyond ease, security, and avoidance of pain,” Orwell wrote. This assumption, he warned, left democratic movements vulnerable to authoritarian appeals that understood something deeper about human psychology.

The 2024 election between Kamala Harris and Donald Trump played out exactly as Orwell predicted: a contest between technocratic competence promising comfort and security, versus authoritarian spectacle offering struggle, identity, and belonging. The result demonstrates why liberal democracies continue to misunderstand their own vulnerabilities.

The False Promise of Rational Politics

Harris embodied everything Orwell identified as the progressive blind spot. Her campaign promised good governance, policy expertise, and rational solutions to complex problems. She offered voters “ease, security, and avoidance of pain”—the very things Orwell suggested weren’t enough to satisfy human psychological needs.

In her post-election memoir “107 Days,” Harris reveals the depth of this miscalculation. She attributes her loss primarily to insufficient time, believing that with more days she could have better explained her economic vision and forged stronger connections with voters. This response perfectly illustrates Orwell’s point: the assumption that better policy explanations and more rational arguments would have solved the problem, that is, would have… attracted more voters.

But as Orwell observed, “human beings don’t only want comfort, safety, short working-hours, hygiene, birth-control and, in general, common sense; they also, at least intermittently, want struggle and self-sacrifice, not to mention drums, flags, and loyalty-parades.” Whilst people may not directly yearn for these things, they have proved to be very susceptible to them.

The Spectacle Alternative

Trump understood what Harris missed. His campaign didn’t primarily offer policy solutions—it offered identity, spectacle, and belonging along with its traditional grievances of the middle class being left behind. The rallies, the flags, the chants, the sense of being part of a movement larger than oneself. Where Harris promised competent administration, Trump offered cultural transformation. Make America Great Again. Indeed.

This wasn’t accidental. Trump’s political operation tirellessly engaged in “Dark-Sky Cultural Monument building”—the systematic construction of identity markers that create powerful ingroup/outgroup dynamics. Christianity, nationalism, traditional gender roles, and racial identity became Cultural Monuments that millions of Americans could rally around, regardless of their material self-interest.

Orwell saw this dynamic clearly in the 1930s, noting that authoritarian movements “enhanced their power by imposing intolerable burdens on their peoples.” The appeal wasn’t comfort—it was meaning. Where democratic socialism said “I offer you a good time,” fascist movements said “I offer you struggle, danger and death,” and entire nations responded with enthusiasm. (They threw themselves at you-know-who’s feet.) I know, this comparison can be taken only so far to be useful. But you can see the parallels. Now let’s look between the ears at that 4 million-year-old bundle of neurons.

The Psychology Behind the Politics

The Harris campaign’s fundamental shortcoming lay in treating politics as primarily rational rather than emotional and tribal. Her team prepared for contested results, legal challenges, and policy debates—”everything, it seemed, except the actual result.” This preparation reveals a worldview that sees politics as a technical problem rather than a psychological and cultural phenomenon.

Harris wrote that when she was asked on “The View” what she would have done differently from Biden, she couldn’t think of a single thing. This wasn’t a failure of imagination—it was the logical endpoint of technocratic thinking that assumes good governance speaks for itself. But as Orwell understood, governance is only one dimension of political appeal. She did not want to “embrace the cruelty” of her opponent. Right. Post-hoc explanations are easy to spot, wouldn’t you say?

The deeper issue isn’t Harris’s individual failings but the systematic blindness of liberal democratic movements to what Orwell called the “military virtues”—not necessarily violence, but the human need for purpose, sacrifice, and collective identity that transcends individual comfort and genuine statecraft. I am not saying that the process of governing is identical to the process of campaigning. Orwell could not have anticipated the elevated spectacle of TikTok, Twitter/X and Facebook, with politics turbocharged by algorithms, but the framework that Orwell described fits the new model of attention-getting and rage-baiting. The loyalty marches may be virtual, but they exist- and they constitute yet another vulnerability that liberal democracy must contend with.

Cultural Monuments vs. Policy Platforms

Trump’s success demonstrates how Cultural Monuments function as political weapons. These aren’t just symbols—they’re inherited belief systems that operate like Cultural DNA, shaping identity at levels deeper than rational thought, embedded cultural programming present since childhood, even before childhood, formed by the culture being inherited in the distant past. When Trump held up the Bible at St. John’s Church or wrapped himself in the flag, he wasn’t making policy arguments. He was activating powerful group psychological programmes embedded in American culture itself. He was channeling the machinery of identity. He was signaling shared values- on the absolute deepest level- those of the fundamental building blocks of American society: the Cultural Monuments of Christianity and American Nationalism.

Harris, by contrast, offered policy platforms. Where Trump exploited identity and belonging, she provided competence and expertise. Where he offered cultural transformation through struggle, she offered incremental improvement through administration. Government by Kaizen. Small steps and continuous improvement.

The asymmetry was stark: one side activated deep psychological needs for meaning and belonging, while the other assumed rational self-interest would prevail. Orwell predicted which approach would prove more powerful all the way back in 1941. Will. We. Ever. Learn?

The Liberal Democracy Trap

This dynamic reveals a fundamental vulnerability in liberal democratic thinking. The very qualities that make liberalism appealing—rationality, predictability, tolerance, incremental progress—also make it psychologically insufficient for many people. Liberal democracy promises good governance but struggles to provide the meaning, identity, and belonging that authoritarian movements offer in abundance. Movements that are almost defined by who they exclude. Like the American Ivy-League schools conservatives love to hate- defined not by who they include but who they exclude, that of 99.999% of Americans, most of whom are red-blooded, white-skinned and may be holding a grudge.

As Orwell noted, “Fascism and Nazism are psychologically far sounder than any hedonistic conception of life.” This doesn’t make them morally superior—quite the opposite. But it acknowledges that they understand human psychology in ways that purely rational politics often miss.

The danger lies not just in external authoritarian threats, but in liberalism’s consistent failure to recognise these deeper psychological currents. When democratic movements assume people primarily want material comfort and rational governance, they leave vast psychological territories undefended. I don’t know how to fix that, my goal here is to point it out to you, my dear reader.

The Identity Politics Paradox

Ironically, while conservatives criticise “identity politics,” Trump’s movement represents the most successful identity politics campaign in recent American history. The difference is that Trump activated majority identities—white, Christian, native-born American—while progressives focussed on minority coalition building and the leftovers of the early-aughts’-starry-eyed-American-urban-scene, the Democratic city political and cultural centres: the so-called “Obama machine.”

This reveals another Orwellian insight: majoritarian identity politics doesn’t feel like identity politics to those within the majority. It feels like defending normalcy, tradition, and common sense. The Cultural Monuments of white Christian Nationalism become invisible to those who benefit from them, appearing as natural order rather than constructed identity.

Harris’s campaign, despite its policy focus, was constantly forced to navigate identity questions precisely because her existence as a Black woman challenged traditional assumptions about who could hold power. Meanwhile, Trump’s identity as a white male seemed neutral, natural, and majoritarian, allowing him to present his cultural appeals as universal rather than particular. Trump’s constant questioning of her declared race was calculated to exploit division: “She was always of Indian heritage, and she was only promoting Indian heritage. I didn’t know she was Black until a number of years ago, when she happened to turn Black, and now she wants to be known as Black. So I don’t know, is she Indian or is she Black?” It was almost too easy for Trump. His base should have recoiled in disgust. Instead, piled into the Colosseum, they could not look away as Trump pulled out the familiar sword. After witnessing the grotesque spectacle, his followers signaled their approval.

This, we have seen before. I’m sure you have not forgotten. Trump pulled the same stunt on Obama’s birth certificate, giving his supporters ‘Birtherism’ to rally around. When. Will. We. Learn?

The Enforcement Mechanism

Cultural Monuments don’t maintain themselves—they require enforcers and defenders who treat criticism as personal attack- the blasphemy police in other words. Trump’s political genius lay in turning millions of Americans into active defenders of his Cultural Monument project. When critics challenged his appeals to Christian Nationalism or white identity, supporters felt their own identities under assault.

This created a self-reinforcing cycle where political criticism became cultural warfare. Policy disagreements transformed into existential battles over American identity itself. Harris found herself arguing not just against Trump’s policies but against deeply embedded cultural programming that defined American authenticity in ways that excluded her from the start. Is there any turning back from this? I am not hopeful. Not after the events of the Summer of 2025.

The Time Trap

Harris’s focus on insufficient time reveals the deepest misunderstanding. She believed that with more days, she could have better communicated her vision and connected with voters. But this assumes the problem was informational rather than psychological.

As Orwell understood, the appeal of authoritarian movements isn’t rational—it’s emotional and tribal. More time for policy explanations wouldn’t have addressed the human need for meaning, struggle, and belonging that Trump’s movement provided. As Carlos Lozada pointed out: If anything, Harris might have benefited from even less time, before the initial excitement of her candidacy gave way to the reality of traditional Democratic messaging.

Beyond the Comfort Zone

The challenge for liberal democracy isn’t to abandon its core values but to recognise that rational governance alone cannot satisfy human psychological needs- at least not for those who need to feel that they were not left out. People don’t just want good policies—they want to feel part of something larger than themselves and that reflects their own identity, to struggle for meaningful causes, to belong to communities that transcend individual interest but do not clash with their own interests. At least not directly.

Orwell didn’t suggest that the desire for struggle and belonging was inherently bad. The problem arose when these legitimate human needs were captured by movements that channeled them toward exclusion, oppression and violence. The question for democratic movements is whether they can provide meaning and identity without sacrificing their commitment to pluralism and human dignity.

The Warning Unheeded

Orwell’s insight from 1941 remains painfully relevant: progressive movements that assume humans primarily want comfort and security will consistently lose to movements that offer struggle, identity, and belonging, regardless of their policy merits. This isn’t because people are irrational—it’s because they have psychological needs that purely technocratic politics cannot address. Harris was easily labelled as woke, liberal, and out of touch with the majority of white christendom. This was summed up in a single advert- “Kamala is for they/them, President Trump is for you”.

The 2024 election wasn’t primarily about inflation, immigration, or any specific policy issue. It was about competing visions of American identity and belonging. One side offered competent administration of the status quo. The other offered cultural transformation through collective struggle against perceived threats to traditional identity. We even knew that this change agent was a deeply flawed human being. Millions of Americans supported him anyway.

Harris’s post-election analysis focuses on time constraints and messaging failures because it emerges from a worldview that sees politics as primarily rational. But as Orwell warned, this assumption leaves democratic movements perpetually vulnerable to authoritarians who understand that humans need more than good governance—they need meaning, identity, and the sense of participating in something larger than themselves. Further, they are susceptible to cultural entrepreneurs who gain followers by exploiting natural divisions in nonhomogeneous populations such as the United States of America.

Until liberal democracy learns to address these deeper psychological needs and vulnerabilities without abandoning its core values, I fear it will continue to lose ground to movements that offer spectacle, struggle, identity and belonging over competence and rationality. The question isn’t whether people should want these things—it’s whether democratic movements will learn to either predict and compensate for these needs or provide for them before authoritarian alternatives fill the void.

The warning was clear in 1941. It remained unheeded in 2024. The consequences are playing out in 2025.

So the question remains, how can liberal democracy address meaning, belonging and identity without lapsing into authoritarianism based on majoritarian exclusion?

-Devin Savage